In Depth: Hubei’s Other Cities Offer Lessons on Battling the Coronavirus

|

Over two months have passed since the new coronavirus, now spreading around the world, was first identified in Wuhan, Central China’s Hubei province.

It remains unclear where exactly the virus came from, but where the battle against it should end is becoming clear.

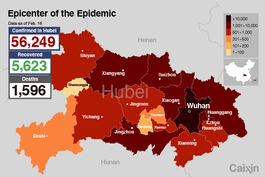

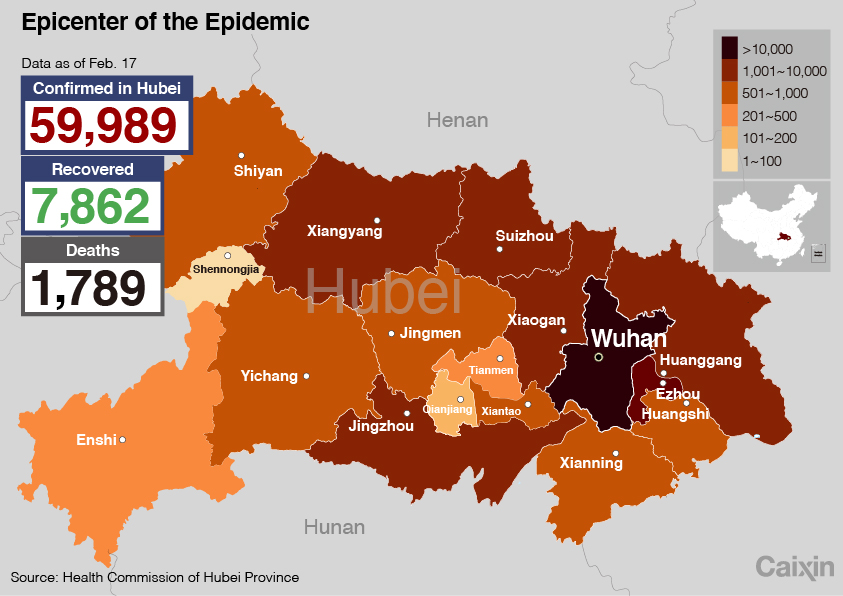

More than 70,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19 have been reported in China as of Tuesday. New cases outside Hubei have been falling for two weeks, suggesting a positive trend in the fight against the highly infectious coronavirus. However, in Hubei, nearly 15,000 new cases were recently reported on a single day — Feb. 13 — making it clear that it’s still too early to hope the battle will soon be over.

Hubei is the key to beating the virus, because if it cannot be contained in the province, it could continue spreading to adjacent regions and the rest of the world.

While Wuhan is the epicenter of the outbreak, it is not the only place worthy of notice. The provincial capital cut off transportation to the rest of the world on Jan. 23, but a large proportion of its residents had already left for 16 other cities in Hubei to celebrate the Lunar New Year, the country’s most important holiday.

Many who traveled from Wuhan to the other cities had been infected without knowing it. It wasn't until adjacent cities such as Huanggang disclosed that they had thousands of coronavirus patients that people realized the entire province — not just Wuhan — was in trouble.

|

The public health crisis has tried the capabilities of those cities, many of which were much less prepared than the provincial capital, with far less medical resources given the province’s steep economic inequality. For example, Wuhan had 3.42 doctors for every 1,000 residents at the end of 2018, but in Xiaogan, the city with the second-most confirmed cases after Wuhan, there were fewer than two doctors for every 1,000 people.

Medical resources are concentrated in China’s metropolises, with smaller cities more vulnerable when the epidemic hits.

Caixin interviewed people across Hubei, including officials, medical professionals, business people, community workers, patients and uninfected citizens, to figure out what helped the virus spread in some cities, and how others have escaped relatively unscathed. Three examples offer valuable insights.

|

Huanggang: The second epicenter

Huanggang, a city just 50 miles east of Wuhan, was the second city in Hubei to officially announce confirmed cases of the coronavirus.

With a population of 7.4 million people half an hour away by bullet train from the provincial capital, the city exchanges a lot of traffic with Wuhan. Huanggang, however, is much less developed in terms of its economy and governance. Much of its population works elsewhere during the year, and Wuhan is their transfer station on the way home for the Lunar New Year holiday.

On Jan. 22, the day before its lockdown, Wuhan recorded its highest daily outflow of people, and 14% of them headed for Huanggang. The local government estimated that around 600,000 to 700,000 people returned to the neighboring city from Wuhan for the holiday.

Huanggang has received much less attention than Wuhan in the battle against the coronavirus, but it is one of the most affected cities by far, with the second-highest number of deaths after Wuhan and the third-highest number of confirmed cases in the province. As of Sunday, Huanggang had a total of 2,828 confirmed cases, including 84 deaths.

Huanggang took notice of the epidemic earlier than many realize. On Jan. 21, more than a month after the Wuhan Health Commission reported its first case of viral pneumonia, Huanggang announced that it had 12 confirmed cases of pneumonia caused by the new virus. But documents from an internal meeting in the city’s Qichun county the day before disclosed that there were at least 109 cases in Huanggang by Jan. 19. At the time, county chief Zhan Caihong warned her team that “significant changes have emerged in the outbreak, and the chances of it spreading are now much higher.”

Caixin also learned from a source working for the city’s health commission that the municipal department had already formed a special group and discussed the infections during a video conference ahead of its first official announcement. “(We) didn’t realize it would go this far. We thought it was just an (ordinary) epidemic virus … and (we) could not afford to cause panic in the public,” the source said.

Slow reactions, lack of experience, and indecision from top to bottom in the city’s counties and towns illustrate how unprepared the public health system was. Consequently, the city missed its window for containing the virus. Health officials didn’t take it seriously early on, allowing a large number of suspected patients to become moving carriers until local hospitals were overwhelmed by panicking patients.

By around Jan. 17, the emergency room at a hospital in downtown Huanggang was already swamped with infected patients, but doctors without experience dealing with such a virus treated them as if they had the common cold, a source at the hospital told Caixin. It was worse in the countryside. Hospitals in some rural areas were not informed of any deployment plans from local leaders until Jan. 23, the day Wuhan went into lockdown.

“Huanggang has never encountered such a disaster or disease. We’ve dealt with it poorly,” a district hospital leader said. “If quarantine and medical treatment were taking place from the very beginning as they should have been, there wouldn’t be so many (patients).”

On Thursday, the central government commanded Huanggang and Xiaogan, another badly hit city near Wuhan, to take the same set of measures as Wuhan in terms of lockdown, quarantine and treatment. As of now, its numbers of fever clinics, designated hospitals and beds have jumped after some emergency requisitions, and most patients with suspected cases have been properly diagnosed.

|

Tianmen: Fighting the ‘fatality rate’

A small city about one-third the size of Wuhan with a population of some 1.3 million, Tianmen made headlines on Feb. 8 for having the highest fatality rate of all cities in China.

On Jan. 25, the first day of the Lunar New Year, Tianmen made its first announcement of five confirmed Covid-19 infections. On Jan. 27, it reported 23 confirmed cases, two of which resulted in deaths of the patients. By Feb. 2, a total of 10 patients had passed away, giving its Covid-19 patients a fatality rate of 5.08%. Even Wuhan reported a lower rate of 4.06%, with the provincial average at 2.88%, according to a Feb. 8 announcement in which the provincial government disclosed fatality rates across the province for the first time.

The fatality rate was exceptionally high, and cases of recovery from the virus were rare. It wasn’t until Feb. 5 that the first recovered patient in Tianmen was discharged from the hospital.

Why Tianmen? Poor medical conditions and a severe shortage of resources in the small city might be the answer.

Although it is only half an hour away from Wuhan by high-speed train, Tianmen is one of the most underdeveloped places in Hubei. In 2018, its GDP was 59.1 billion yuan, second-lowest in the province.

The city’s underdeveloped economy left it without sufficient resources to handle the outbreak. At the end of 2018, Tianmen had 2,549 qualified physicians and 15 hospitals with a total of 6,411 beds, less than 7% of the number in Wuhan. In addition, based on Caixin’s research, cases confirmed in Tianmen were scattered among its towns and villages, but most of the area’s limited medical resources are in the center of the city, making it less likely that patients in the countryside would be treated or quarantined in a timely manner.

Once hit by an epidemic, a small city with poor medical resources becomes immediately vulnerable. Tianmen started to take action against the epidemic after Wuhan went into lockdown, but the virus had already infected quite a number of its residents by then. For many, their condition turned critical because they didn’t receive prompt treatment due to lack of medical resources. That resulted in Tianmen’s exceptionally high mortality rate.

The outstanding fatality rate in the early stages of the outbreak brought about extreme pressures in Tianmen in the fight against the virus.

Under pressure due to the high fatality rate, the city quickly escalated its response. Local officials made their primary goal to “improve the recovery rate and lower the infection and mortality rates.”

The fatality rate from the coronavirus has since gradually fallen, even as the number of confirmed cases has continued to rise. As of Feb. 11, with 10 deaths and 293 cases, Tianmen’s fatality rate had fallen to 3.41%, ranking fourth in Hubei.

|

Qianjiang: A rare positive example

Among dozens of cities hit by the epidemic, one city in Hubei stands out as a rare bright spot.

Qianjiang, a densely populated city on a convenient transportation route only 90 miles from Wuhan, had an unexpectedly low total number of coronavirus infections — 166, the lowest in the province outside the mountainous region of Shennongjia.

Qianjiang did better than others because of quick decision-making by the local government and an existing culture of “self-governance.”

Qianjiang demonstrates that responding just a few days faster can make a big difference. Wu Zuyun, Qianjiang’s party chief, first heard of the virus when he was attending a province-wide government meeting in Wuhan in mid-January. “The mayor and I had a feeling that this could be huge,” Wu said. “So we took preemptive measures, even if that meant taking some risks by not following the rules.”

Qianjiang took measures earlier than most other cities in Hubei, putting its first group of 32 suspected patients into quarantine on Jan. 17. On that day, the Wuhan health authority’s official report was still saying there was “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.”

Wu didn’t elaborate on what risks were taken by “not following the rules.” But such preemptive action could likely have had both economic and social costs. Accordingly, if the disease had turned out to be a false alarm, the decisionmaker would have to take responsibility. Qianjiang’s leaders took a chance by walking their own path, which saved the city from a tremendous loss.

A close study of the official Qianjiang newspaper didn’t show any mention of the disease until Jan. 23, indicating that Wu and his team made a careful decision to quietly take action without waiting for orders from above.

After the provincial leaders finally pulled the alarm, Qianjiang quickly followed up with stricter control measures. In addition to traffic lockdowns, every five families made up a control unit for which one controller was assigned. A citizen in Qianjiang also told Caixin that each family can only send one person to go shopping every three days.

Such strict measures could have triggered complaints from local residents like they had in other places, but not in Qianjiang. That’s partly thanks to a tradition of “self-governance” among its residents.

The city was cited as an example of “villager autonomy” by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 1999 for its experiments in rural democracy. Following such a tradition, residents in Qianjiang have a higher awareness of autonomous governance, which translates into a smoother interaction with the local authorities.

While most cities in Hubei were sending out cries for help, Qianjiang actually donated supplies to Wuhan twice. Its donations included 100,000 medical masks and necessities like rice and vegetables.

As the situation in Hubei remains dire, the rare example of Qianjiang offers a lesson. If only there were more cities in the province that acted early, before it was too late.

Denise Jia, Zhang Fan, Zhang Zizhu, Huang Yuxin, Hu Yue, Wu Hongyuran, Tang Ailin, Wang Mengyao, Huang Huizhao, Zhou Tailai, Huang Yanhao, Chen Lijin, Zeng Linke, and Cao Wenjiao contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Isabelle Li (liyi@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China’s Balancing Act to Keep Its Social Security System Afloat

- 2China’s Macro Leverage Ratio Rises to 294.8% Despite Slower Borrowing

- 3TikTok Shop Faces Regulatory Hurdles in Bid to Become No. 1 in Vietnam, Expert Says

- 4U.S. Lawmakers Seek Sanctions on Chinese Carmakers for ‘Aiding Russian Military’

- 5Hillhouse Unit to Buy Back Longi Green Energy Shares Amid Probe

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas