Driven by Algorithms, Food Giants’ Delivery Riders Win Small Reprieve

China’s food delivery giants are facing a reckoning after a viral article highlighted the grueling lot of their delivery riders, and the tyranny of the algorithms that control their lives.

The six-month investigation by Chinese-language magazine People lays out in grim detail the human cost of a delivery system run by machines calibrated to maximize efficiency and profit.

It shows how the pressure to meet tight deadlines pushes riders to the brink, forcing them to zip around streets and alleys on electric bikes at hair-raising speeds, breaking road rules to avoid being penalized.

The expose, which went viral on social media under the title “Delivery Rider, Stuck in the System,” also describes how they and members of the public are regularly maimed or killed in resulting road accidents.

Meituan-Dianping, the focus of the story, issued an apology late Wednesday that pledged to give drivers an additional eight minutes per delivery. It also said it would reduce penalties and extend delivery times further in hazardous weather.

Ele.me responded the same day by launching a function to allow users to give their driver an additional five or 10 more minutes, saying “Everyone who works hard deserves to be treated with respect.” The response was criticized on social media for appearing to shift blame and responsibility to users.

But both responses were broadly seen as cosmetic fixes in an industry where labor regulations have fallen way behind, as the market has concentrated around a couple of firms that squeeze delivery costs by using third-party labor contractors.

Squeezing costs

For online takeaway firms, delivery riders are the largest single cost, and the biggest source of risk. There has been little motivation for companies like Meituan and Ele.me to reduce their burdens.

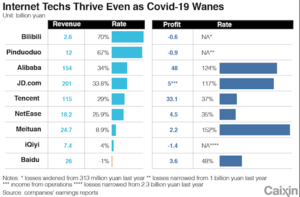

In 2019, Meituan spent 41 billion yuan ($5.9 billion) on “rider wages,” equivalent to 74.8% of its total food delivery revenue. Centralizing deliveries and reducing the cost of each delivery has been the only way for the firm to put downward pressure on those costs, and it’s how the company was finally able to turn profitable last year.

Meituan now has more than 2.95 million delivery riders on its books. The industry as a whole gained 1.39 million new ones just this year as the epidemic left people out of work.

In other areas the company has splurged. To gain the enormous 67% share of China’s food delivery industry it booked in the first quarter, the company has relied on generous subsidies.

Meituan had an almost 40% edge over its rival Ele.me during the pandemic, according to research firm Trustdata. Market dominance and customer loyalty have delivered both firms the upper hand in negotiations with restaurant businesses, which are now forced to pay commissions and sign exclusive contracts that agree not to list on competitor platforms.

Market dominance has also given the delivery firms an edge when negotiating with the labor hire companies they now rely on for riders.

In 2017, Meituan and Ele.me both gave up building their own rider workforces, and began outsourcing. While riders from both companies may wear different colored uniforms, the prospectus of newly-listed labor hire company Quhuo Ltd., which raised $33 million with a Nasdaq IPO in June, shows they’re often provided by the same firm.

It is companies like Quhuo that actually manage the riders, at arm’s length of the delivery firms, reducing their liability and taking a cut in return. The “rider wages” section of Meituan’s financial report is not money paid to riders, but to firms like Quhuo.

People magazine interviewed Sun Ping, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who said the shrinking time targets set for delivery riders encourages them to speed, run red lights, and engage in the sort of hazardous behavior that causes road accidents.

Data from Shanghai Public Security Bureau bear this out. In the first half of 2019 alone, express delivery and food delivery drivers were involved in 325 road accidents, with five deaths and 324 injuries. Ele.me and Meituan drivers accounted for around a third each.

Vicious cycle

Another way Meituan and Ele.me cut rider costs is with self-optimizing algorithms to help them pack in more deliveries. That may sound impressive, but the investigation shows they’re not all they’re cracked up to be. GPS tracking often fails and route calculations don’t account for temporary obstacles. It can make meeting targets a superhuman feat.

Meanwhile the very process of self-optimization — the system autonomously and continuously adapting to new data and information — has created a vicious cycle where drivers race the machine to meet time goals only to see them reduced the next time around.

In 2015, Meituan began replacing human mediators at its delivery stations with a digital network powered by artificial intelligence. It generates the most effective plans to distribute orders to couriers, based on restaurant locations, food preparation time and riders’ driving speed. Two years later, Ele.me made a similar move by acquiring delivery service Baidu Waimai, later rebranded as Star.ele.

In an apparent attempt to give more transparency to customers, delivery platforms require couriers to turn on GPS tracking and report real-time steps from arriving at the restaurant, to picking up food and to delivery completed.

Customers are granted absolute power in a hierarchy where their reviews directly affect couriers’ income. Bad customer reviews cut into couriers’ commission fees and “five-star” feedback delivers a bonus. Riders have little chance to appeal if they are unfairly complained about or penalized for no apparent reason. And they can’t rate their customers.

In 2019, Meituan reported a 94.2% year-on-year jump in profit to 10 billion yuan in the food delivery sector. This was attributed to “higher order density, refinement of our proprietary dispatching system algorithms,” the company said in its yearly financial report.

Contact reporter Flynn Murphy (flynnmurphy@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR